When the pandemic began two years ago, New Jersey had the nation’s highest COVID-19 death rate in prisons. Incarcerated people, fearing for their lives, joined with their families, activists, and advocates to get the Public Health Emergency Credits Law (PHEC) passed and signed. It allowed people nearing their release dates to leave prison up to 8 months early, and it has saved lives.

The latest New Jersey Department of Corrections (NJDOC) numbers shared with the ACLU-NJ — which include 852 people released on March 13 and another 870 over the next several months — show just how significant the impact has been for public health, for reforming our criminal legal system, and for making lives better.

Since the Public Health Emergency Credits Law went into effect less than a year and a half ago, more than 6,600 people have been released early under it, according to the New Jersey Department of Corrections. Once the last wave of people come home, 8,251 people will have been released since March 2020 as the result of both the emergency credits and legal advocacy that preceded the law.

PHEC was passed for a specific reason — to address the crisis of a highly contagious pandemic. But it has taken important steps to confront a much longer crisis: over-incarceration and the criminalization of people of color.

New Jersey’s prison population has dropped 42 percent since March 2020, totaling 12,947 as of January 2022 according to New Jersey Department of Corrections data. Recidivism numbers have been impressively low, with people released early getting rearrested at lower rates than others who have served their entire sentence. That’s on top of the fact that New Jersey’s recidivism rates are already below the national average.

Even including our state’s federal prisons, New Jersey’s prison population dropped by one-third from end of 2019 through 2021, second only to West Virginia, according to a WNYC’s reporting on a new Vera Institute report.

The Marshall Project’s data concerning COVID-19 in prison has shown that New Jersey’s numbers are now among the lowest, a reversal from the early days in which our numbers were among the gravest.

At its heart, the public health emergency credits law is not a pandemic policy. It’s a policy about humanity. It’s a policy recognizing that no one, including incarcerated people and their families, deserves gratuitous suffering. But that was true long before the first case of COVID-19, and it’s true for the daily injustices of over-incarceration that will exist long after the last public health emergency of the pandemic is over.

As we come out of the pandemic, we have a responsibility to see the humanity in incarcerated people in all circumstances, not just unprecedented circumstances. The credits under PHEC were introduced to account for the hardship of serving time during a public health emergency and to slow the speed of infection by allowing greater social distance, but it’s just one part of a constellation of policies that are necessary to address the injustices of incarceration and over-criminalization.

Before the latest wave of releases, ACLU-NJ Executive Director Amol Sinha put the impact of the emergency credits into stunning perspective: “New Jerseyans got back 2,759 years — more than 1 million days — of freedom and opportunity.”

Our state, which is the only one to have implemented a policy of public health credits so fully, has a special responsibility to lead the way, as the state with the nation’s worst disparity in the incarceration of Black and white people in state prisons. But all states have a responsibility to end the needless brutality of overincarceration.

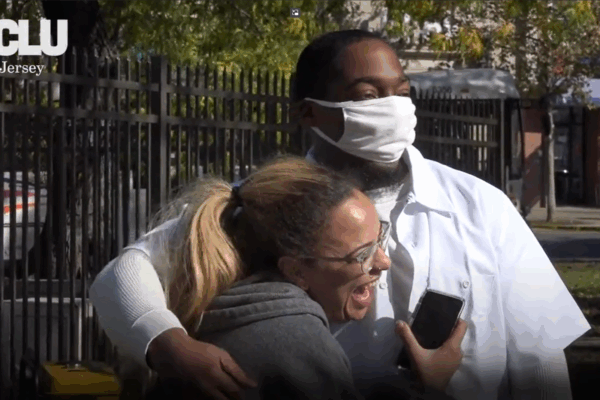

The image of more than 8,000 people averting the danger of the pandemic in New Jersey prisons casts a shadow of the hundreds of thousands of people across the country who instead added to the exponential toll of COVID-19’s spread.

The 8,000 people in New Jersey had a smaller chance of enduring the fate that befell Rory Price, who died on May 1, 2020, just weeks before his scheduled release date. In turn, exponentially more people inside had a better shot at survival.

It may have taken a pandemic to shed light on the vulnerabilities we all share — susceptibility to suffering and pain, worrying for loved ones, grief in the face of death — but our humanity exists independent of a pandemic. PHEC has shown the urgency of decarceration, and it shows a model for how we can begin to do it on a larger scale.